A Payphone and a Briefcase

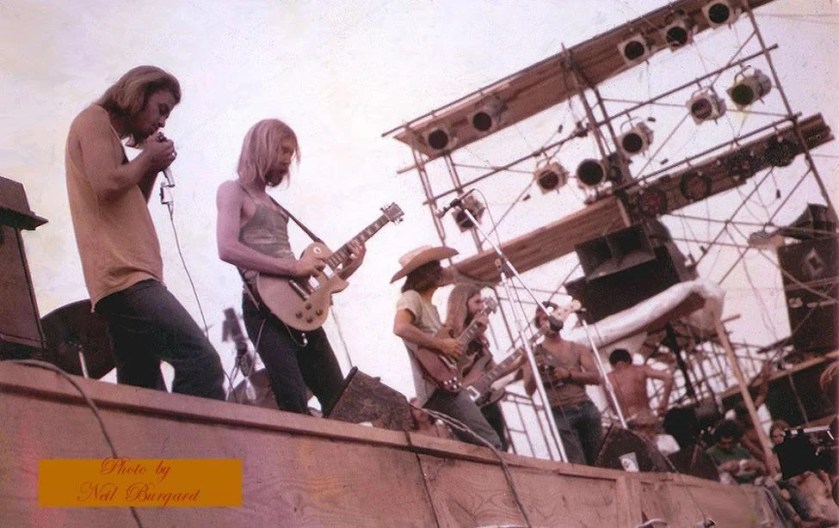

On a hot Friday, July 3, 1970, Willie Perkins is pacing back and forth in front of the performer’s entrance to a raceway in middle Georgia. Willie just turned 30 in April and he’s now the new Road Manager for The Allman Brothers Band (ABB), the unofficial headlining act of the second annual Atlanta International Pop Festival being held at the raceway in Byron, Georgia.

The ABB is a relatively unknown, unproven band and this gig opening a festival where B.B. King, Jimi Hendrix, Grand Funk Railroad, and others will perform could be the break the band needs.

Yes, Byron isn’t Atlanta, despite the festival’s name. Instead, Byron is a small town straddling I-75 about 90 miles south of Atlanta, in the exact heart of Georgia, and only minutes from Macon where the ABB records at Capricorn Records and eventually lives in a Tudor mansion called The Big House (currently a museum of all things ABB).

As Willie continues to pace, the band will be going on stage soon, the crowd is growing quickly, and there’s no way to communicate with Duane Allman, the band’s founder and incredibly talented guitarist who hasn’t shown up. As Willie would later note in his book Diary of a Rock and Roll Tour Manager, “Remember, there were no laptops, internet, or cell phones.”

Willie’s only option is to pace and watch nervously, knowing Duane is driving up from a recording session in Miami after assuring Willie he’d be there. But I-75 is a parking lot for miles and miles as hundreds of thousands of music fans make their way to the festival.

Since taking on his new job with the ABB in May, Willie has been on a crash course of on-the-job training, self-taught no less, and he’s determined to do an excellent job. They’ve started a betting pool at Capricorn records based on Willie’s ability (or not) to keep his job for 100 days.

Originally, Willie wasn’t even sure what the road manager role entailed. He wanted the job, though, and he knew his most important task was ensuring all band members showed up, and showed up on time.

Willie is feeling the pressure of missing bandmate Duane, the guy who started the entire ABB adventure, the guy who plays like no other and inspires countless people, then and now, to pick up the guitar and learn to play.

Duane wanted this rock career; he’d been playing guitar, informally studying music, and expanding his musical connections, along with his brother Gregg, since he was 11 and Gregg was 10 years old! Those two brothers practiced, experimented, and learned from each other with a rare dedicated passion.

Heck, Duane is only 23 years old as he’s making his way to Byron, Georgia, on I-75. 23! That’s impossibly young for someone so talented. Before forming the ABB in 1969, Duane was a session guitarist for Rick Hall of Fame Recording Studios in Muscles Shoals, Alabama, recording with many great artists of the time, such as Clarence Carter, Wilson Pickett, and Aretha Franklin.

Duane’s youth makes him resourceful; through his early struggles he’s learned that taking risks can sometimes be rewarding. As traffic is standing still on I-75, Duane abandons his Ford Galaxy at a truck stop and hops on a motorcycle driven by a stranger, now a new friend, who is committed to getting Duane to Byron, Georgia, and to the Atlanta International Pop Festival on time. Willie’s gate-side vigilance pays off when he sees Duane dismount the motorcycle just in time to get on stage for the festival’s opening. Huge relief!

Today, Willie is rightfully proud that the ABB never missed a performance, unless someone was severely ill.

The original ABB members included:

- Duane Allman – Lead and Slide Guitars

- Gregg Allman – Piano/B3 Hammond Organ, Vocals

- Butch Trucks – Drums

- Jaimoe – Drums

- Dickey Betts – Lead Guitar, Vocals

- Berry Oakley – Bass Guitar

Crew Members included:

- Kim Payne

- Red Dog

- Mike Callahan

- Joe Dan Petty

The band’s members and crew may have been typical models of young, male rock groups caught up in the novelty and allures of fame, drugs, and sex, but professionally they were reliable and sometimes performed gratuitously, even saving a music promoter’s tush every now and then, like they had done at the Cosmic Carnival in Atlanta a month before the pop festival. Many of the scheduled performers had dropped out because of low ticket sales at the Atlanta stadium. But the ABB knew they couldn’t disappoint an Atlanta crowd so Willie renegotiated their fee and they performed, with Duane spontaneously deciding and announcing from the stage that the band would play for free in Piedmont Park the next day, which they did.

The ABB’s involvement with free concerts at Piedmont Park started with an invitation from Colonel Bruce Hampton, a unique musician at the center of the Atlanta music scene when live music was nil in Atlanta bars and venues. Colonel Bruce Hampton never really gained widespread fame or fortune but he found deep loyalty and admiration from the people who knew him. He was Atlanta’s center of gravity for all things musical and he was a friend to the ABB in their beginning.

Scott Freeman, author of the Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band (the 1995 seminal publication about the band and “Southern Rock” roots), wrote a 2007 Creative Loafing article about the Colonel that’s a must-read for music enthusiasts of all genres.

The ABB had support from people like the Colonel and Phil Walden, owner and producer at Capricorn Records, as well as encouragement from their early fans. However, much of the credit for the ABB’s reliability and rise to massive stardom goes to Willie Perkins, while the spirit of community and giving back to fans started with Duane and Gregg, permeating the group over time and drawing more fans into their orbit.

How Willie became the ABB’s road manger is a wild tale, like much of what transpires with the ABB over the next few decades. The short version: Willie’s friend and the ABB’s original road manager, Twiggs Lyndon, stabbed and killed a club owner in New York for shorting the band on their fee, and while in jail awaiting trial Twiggs recommended Willie as his own replacement. Willie had long wanted to work on the road crew and Twiggs had promised him the next open spot on the road crew, but Willie never dreamed Twiggs would lose his job, and a man would lose his life, so Willie could join the ABB.

Thus, in 1970, began Willie’s wild-ride career in the music industry as a vital part of a band of hippies who would make history, something he had dreamed about as a boy growing up in Augusta, Georgia, in the 1940s, while watching weekly Westerns in the theater, and as a teen listening to soul music broadcast late-night by WLAC from Nashville.

The ABB’s magical mix of six stellar musicians (plus psychedelic drugs, according to Dickey Betts) brought the new bluesy rock sound while Willie brought his business acumen, banking knowledge, and love of R&B. Together, they changed music, and themselves, while bringing the South to the world.

Influences

What drew Willie, an Atlanta banking auditor with a bachelor’s degree in business administration and seven years’ of bank audit/fraud experience, to the ABB? He was on a fast track to success with the Trust Company of Georgia Bank; upper management had him in their sights for continued advancement. But Willie gave it up, much to his family’s befuddlement, for a chance to spread the ABB’s music to the masses.

In his book Diary of a Rock and Roll Manager, Willie writes about his reaction to hearing the ABB play for the first time at Piedmont Park in 1969:

“I had a feeling their amazing talent would propel them to the pinnacle of success and wanted to help them in any way possible.” (pg. x)

In his first book No Saints, No Saviors, Willie writes:

“I simply had a feeling that this would be one of the biggest bands in America. America just didn’t know it yet.” (pg. 11)

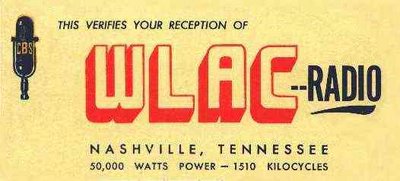

Willie had heard plenty of good music in his life up until hearing the Brothers. His favorite music throughout his teens in the 1950s was R&B, the hits of Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and many others coming to Augusta, Georgia, through the nighttime airwaves at 50,000 watts all the way from WLAC in Nashville, Tennessee, 1510 on the AM dial. WLAC was started by, and named for, the Life & Casualty Insurance Company in the 1920s.

“WLAC was broadcasting to an audience of rural blacks,” Willie recently tells me while he and I enjoy lunch at H&H Cafeteria in Macon, Georgia, the restaurant where founders Mama Louise Hudson and Mama Inez Hill fed the ABB before they were famous (sometimes for free). Willie has been eating at H&H for more than 50 years now, and their soul food is still good, and still good for the soul. Between bites of his salmon croquette, Willie continues, “And along with the blacks in the rural south, a lot of us white boys were listening.”

Willie can still hear the voices and quote the words of his favorite white DJs: John R., Gene Nobles, the “Jivin’ Hoss Man,” and sometimes even Wolfman Jack coming in from Del Rio, Texas.

In a Nashville Tennessean article titled WLAC: The Powerhouse Nashville Station That Helped Introduce R&B to the World, writer Matthew Leimkuehler quotes Michael Gray of the Country Music Hall of Fame: “The influence that WLAC wielded in the R&B world, it just can hardly be overstated. It provided a shared cultural experience for millions of African Americans while also transforming the lives of millions of white teenagers.”

“Stores like Ernie’s Record Mart and Randy’s Records would advertise on WLAC,” Willies says, “selling sets of 45s and 78s of the R&B music being played. I bought those records back then.”

By selling those packaged records in the late 40s, Randy’s Records and WLAC inadvertently started the music mail order business. And Willie was part of that!

Sampson on Spontaneous Lunacy’s website tells the story of WLAC’s rise and fall in an article titled WLAC, Randy’s Record Shop and the Birth of the Mail Order Record.

Willie has a juke box in his basement that doesn’t work, but it possibly contains some of those records he bought from WLAC advertisers in the 50s.

“Some of those records may have gone in the divorce, too,” Willie says. “Being on the road so much was rough on marriages. All of us got a divorce at least once, except for Chuck Leavell.”

Willie felt so strongly about WLAC and its impact on his life, and the lives of his contemporaries, that he began crafting an article for Rolling Stone magazine expressing how the late-night R&B programming had influenced teens throughout the south.

“I went back and forth with Rolling Stone on a couple of iterations of the article, getting feedback,” Willie says, “but then I got the job with the band and had to tell the magazine I didn’t have time to finish the article.”

Willie listened to WLAC regularly even though the programming didn’t start until 10pm. Listening to R&B was his religion. His field of study. Maybe, at Piedmont Park in 1969, he recognized the underlying blues and soul in the ABB’s sound, and that’s what drew him in.

Or, maybe Willie recognized in Duane and Gregg fellow children of military officers who had served in WWII. And fellow children of military men who were killed while on active duty. Willie’s father, Army Captain William Hardwick Perkins, Sr., was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 at age 32, taken prisoner by the Germans, died from his wounds in January 1945, and was buried in the Netherlands American Cemetery, posthumously receiving a Purple Heart medal. Willie was five years old when his father died.

Duane and Gregg’s father, Second Lieutenant Willis T. Allman, served with his brother Howard Duane Allman in the army during WWII. They stormed the beaches of Normandy together, and miraculously returned home safely to Norfolk, Virginia, together, becoming Army recruiters after the war ended. However, the day after Christmas in 1949, when Duane and Gregg were three- and two-years old respectively, Willis Allman and a fellow officer, Second Lieutenant Robert Buchanan, were robbed of less than $5 total by a fellow war veteran, 28-year-old Michael Robert Green, who had asked for a ride and was kindly accommodated by the officers.

In a remote, freshly plowed field, Green held the two men at gun point. When Buchanan said, “Don’t shoot us, Buddy,” using a casual term for a friend to de-escalate the tension, he had no idea that Green’s nickname was Buddy. “Too bad for you because you know my name,” Green said. “I have to shoot you.” As Allman resisted, Green shot him point blank in the chest with a German pistol.

Buchanan was able to escape and get help but 31-year-old Allman had died in the interim. Green was apprehended the next day as he slept with a pistol.

Suddenly, as toddlers, Duane and Gregg were fatherless, and their mother Geraldine was a single mother. Although Willie, Duane and Gregg were five or younger when they lost their fathers, completely unaware of the ramifications, growing up without a father is known to have an impact on boys. Did Duane, Gregg and Willie unconsciously recognize each other as fellow members of such a tragic club?

The tragedy of Green’s impact on the Allman family continued for years. Green, who had fought in Italy during WWII as a mine sweeper and bomb de-fuser, was found guilty of murdering Willis T. Allman and sentenced to die in the electric chair. Before his execution date, Green hit a guard over the head with a metal pipe and escaped from jail, but was soon recaptured.

The day before Green was to be executed, Virginia governor Battle commuted his sentence to life behind bars, saying Green had been under psychological stress after serving in the war.

Scott Freeman, in Midnight Riders, writes that Willis’ brother, Howard, contacted the parole board every year to make sure Green was still in jail, but then in 1975 he learned that Green had been set free —a major disappointment for a devoted brother. Green wasn’t executed and he didn’t serve a life sentence. As a free man, he remained in Norfolk, Virginia, until his death in January 2024 at age 100!

Duane, Gregg and Willie, with their mothers’ guidance, did the best they could growing up fatherless in the 50s and 60s. All three of them attended military school.

From a very young age, Duane and Gregg went to Castle Heights Military Academy in Lebanon, Tennessee, enabling Geraldine to attend college and become a certified public accountant. Geraldine went to college on her deceased husband’s military benefits and the family received reduced tuition at the academy because their father had died while on active military duty.

Both Duane and Gregg very much disliked the experience of being in a military school with its rigid schedule, demanding routines and constant fights amongst the students. And, being so young, they naturally missed their parents in a heartbreaking way. It was like being orphaned twice.

In 1957, when Duane was 11 and Gregg was 10, Geraldine completed her college degree, took the boys out of the academy and moved down to Daytona Beach, Florida.

Willie attended high school in the same public military school in Augusta, Georgia, that his father, William H. Perkins, Sr. had attended. He writes about his time at Richmond Academy in No Saints, No Saviors, saying “My dad had been a cadet lieutenant colonel of the school battalion, but I was a lowly buck sergeant squad leader… I tried to be a good soldier but military life was not for me.” (pg. 3-4)

Attending Military School was one more commonality that possibly drew Duane, Gregg and Willie to each other.

In their musical efforts, they were bonded as brothers in getting the ABB’s music out to the world, despite their life circumstances. In fact, the band members and their road crew spent a great deal of time together, sometimes bringing their small families under the roof of The Big House, forming “the brotherhood.” As they built their lives in Macon, the band created a circle that widened over time, comprised of musicians, industry folks and fans. Seems that Gregg might have alluded to the brotherhood (and his Southern raising) when he sang a favorite — May the Circle Be Unbroken — anytime the band jammed.

Living together and hanging together at The Big House allowed the band members to jam spontaneously. “They kept instruments set up so they could just step in and start playing,” Willie says. And when they started playing, they riffed. They improvised and went places with the music they didn’t know they were going. They were on an odyssey to find their sound and their groove… and themselves.

On stage, with each musician a master of his instrument and with their mystical ability to follow each other, the ABB became known as one of the greatest jamming bands of all-time.

Band members could safely afford to lose themselves in the music because Willie Perkins was just offstage, managing the thousands of logistical details that led to the band’s reliability and its ability to be economically creative. Pennies had to be watched. But soon their earnings would go from meager to staggering. And Willie knew just how to manage it.

Willie made a great road manager from the get-go. With his mind for numbers and his skill at managing details, he was just what the band needed. And they all knew it.

“They never understood money,” Willie says, laughing. But Willie understood money and he used his budgeting skills in the early, lean years to ensure the group had what they needed to get by.

Willie kept meticulous records. He had to for tax purposes. But he is naturally a curator and organizer. If you go to The Big House Museum today and look at the pool table on the ground floor, it’s covered in ABB memorabilia; tickets, programs, travel docs, etc.

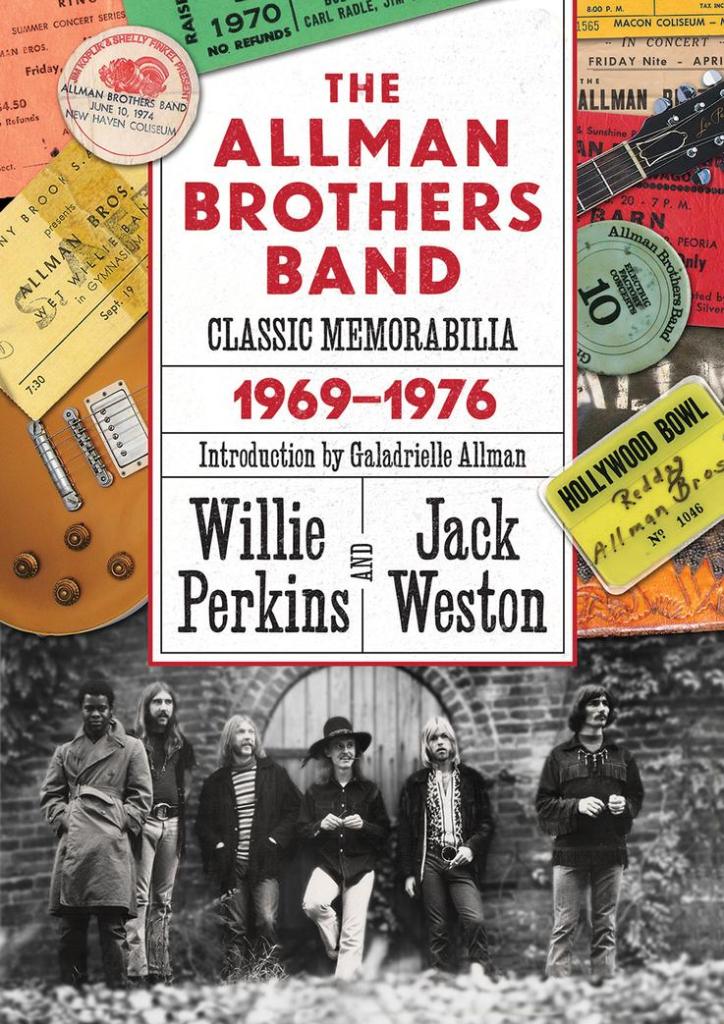

In 2015, Willie got together with Jack Weston, another ABB collector, and they combined their mass of collectibles into Willie’s second book, The Allman Brothers Band Classic Memorabilia, 200 pages filled with photomontages of autographs, apparel, band instruments, concert posters, passes, etc. Some of their stuff is in the museum, but much of it remains in their private collections.

What is a Road Manager?

Plenty has been written about the ABB and its individual members, including in Gregg Allman’s own words in his autobiography My Cross to Bear, which he wrote with Alan Light.

Here, we’re focusing on Willie Perkins and his unique abilities that contributed to the ABB’s tremendous success. It helped that Willie was slightly older than the brotherhood members, had earned a college degree and had business experience in a white-collar job. He also loved music, and loved the ABB’s music, and believed in them.

During his interview for the road manager job, which took place in the band’s camper outside a gig at Georgia Tech stadium, Duane pointedly told Willie how difficult the job would be, especially managing the combined team of nine band members and road crew.

Willie had dealt with fraudsters and bank robbers in his bank job so maybe the brotherhood wouldn’t be as shrewd or cunning. And he really wanted to be part of the band’s success, which he had envisioned from the first time he heard them. So, Willie brought vision and tenacity — some might even say a doggedness — that created stability where stability hadn’t existed amongst the group. There’s even a Facebook group devoted to Willie Perkins with these words in its name: “Solid, Stable Force behind the Original Allman Brothers Band.”

Here is a list of band members and crew, and their ages, when Willie joined in May 1970:

Band Members

- Duane Allman, 23

- Gregg Allman, 22

- Butch Trucks, 23

- Jaimoe (Jai Johanny Johanson), 26

- Dickey Betts, 26

- Berry Oakley, 21

Crew Members

- Kim Payne, 26

- Joseph “Red Dog” Campbell, 28

- Mike Callahan, 26

“They were just babies when they started out,” I say to Willie in awe. “When fame started happening.”

“They were just babies,” Willie repeats.

In 1970, Willie would need his vision and doggedness to do his job without cell phones or even beepers. Managing a touring band took lots of brain power. On the road, all Willie had were pay phones (or hotel phones) and a briefcase, an instrument as important for the band as Duane’s guitar.

In both his books Diary and No Saints, Willie gives descriptions of what he did as a road manager making $140 per week:

- Pre-plan all travel and lodging

- Plan and execute all logistical coordination necessary to transport, house, and supervise and setup of sound, light, and equipment

- Get the band on and off stage at the proper time

- Compute and collect all contractual performance monies due

- Pay all expenses related to the performance, including payroll

- Collect and retain all records and receipts for bookkeeping, auditing, and tax purposes

- Be on call as diplomat, logistician, amateur psychologist, disciplinarian, accountant, liaison with management, etc.

- Get to the next town and do it all again the next day

- Day after day

He also had to keep club owners honest in making payments. They could be shady and sometimes resorted to robbing managers for the very monies they had just paid. Wisely, Willie always insisted on cash BEFORE the band played, and he pulled from his banking experience by telling club owners, “We have a deal with banks. They don’t play rock and roll and we don’t take checks.” (No Saints, No Saviors, pg. 20).

He learned a good bit from Earl “Speedo” Simms, Otis Redding’s road manager who accompanied Willie to his first official gig on Georgia’s Jekyll Island, to show Willie the ropes.

One day of training. That’s all Willie got, but it helped.

Speedo impressed upon Willie the importance of keeping his briefcase, which he had inherited from Twiggs, safe. Speedo even suggested that Willie handcuff the briefcase to water pipes in hotel rooms, which Willie did.

The briefcase was a roaming file cabinet and vault containing records, receipts, contracts and cash. When Willie originally took over as road manager, he spent weeks going through and organizing Twigg’s bookkeeping system and balancing the books. He learned the band was broke and in debt to their record label.

How in the world would he get them out of that hole?

Solid Stable Force

Willie didn’t just get the ABB members out of debt, he eventually coached them on how to put their monies into retirement investments. Financial advisement wasn’t part of his road manager role, but he did it anyway.

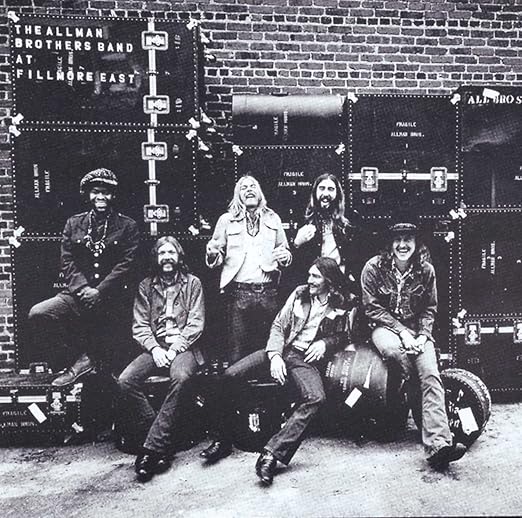

“Duane wasn’t around when the band hit it big, but he knew it was coming,” Willie says of Duane’s death in a motorcycle accident in Macon on October 29, 1971. The group was inching toward stardom when their double LP At Fillmore East sold 500,000 copies in three months that summer. But then, just four days after the album was certified gold, Duane died.

Grayson Haver Currin’s review of At Fillmore East gives an excellent background into the technology used onsite to record the group’s sessions, how much thought and hard work went into each night’s performance and the importance of the Fillmore album (and subsequently the Eat a Peach album, which contains some of those 28 live songs recorded during their final concert at Fillmore East Theater in Manhattan).

Saying the band was devastated by Duane’s death is an understatement.

Just one month shy of turning 25, Duane was already considered by many to be one of the greatest guitar players in the world. As a founding brother of the band who provided the group’s unique sound, continuing the band without Duane’s natural leadership wasn’t a certainty. The brotherhood could have easily dispersed in their grief. No one could replace Duane, and no one did. But then a year later a second tragedy threatened the group’s cohesiveness when bassist Berry Oakley died in a motorcycle accident not far from where Duane had died in Macon.

How much tragedy can one group of young people absorb?

Eventually the group invited pianist Chuck Leavell to join them; his keyboard skills added an element to their sound that had been missing since Duane’s death. Chuck went on to form his own band, called Sea Level, which Willie managed for a while, and then, in the early 80s, Chuck became the keyboardist and musical director of the Rolling Stones, a role he continues to this day. They also invited Lamar Williams to replace Berry on bass guitar.

Through it all — the shows on the road, the recording at Fillmore East, the tragic death of two band members — Willie Perkins was there, offering steadfast support and a guiding hand while going through his own grieving process.

Not only did the band not fold, but it soon experienced super-stardom, along with the money and fame that comes from inspiring people the world over. They were bringing in hundreds of thousands of dollars for one show. Willie kept a tight hold on that briefcase and the checking account.

Eventually, though, the ABB did disband in 1976, followed by Capricorn Records closing in 1979. There were lawsuits and hard feelings between band members and Phil Walden that took years to resolve and get over. The band came back together again and again. Phil Walden took Capricorn Records to Nashville, but that venture eventually failed.

Willie had resigned from the band just before its dissolution in 1976, and he moved up to Atlanta with plans to retire. Soon he realized how much he missed the excitement of managing a band. When Gregg Allman called Willie in the early 80s and asked if he would manage Gregg, Willie instantly said Yes and jumped up and down while on the phone.

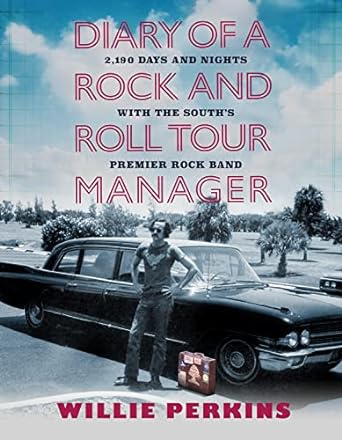

Willie’s first book, No Saints, No Saviors, about his road managing days with the ABB, was published in 2006 by Mercer University Press. He got the call from the press, telling him the book was a go.

“Did you jump up and down,” I ask, “like you did when Gregg called you?”

“No,” Willie says, “I was used to good things happening by then.”

And there it is. Proof of the power of magical thinking. Willie wanted to work with the ABB and it happened. He remained with the group until just before they disbanded and then he worked with Gregg, Chuck Leavell’s Sea Level group and other artists, eventually “retiring” in the early 90s to start Republic Artist Management, his own talent management company, and Atlas Records in Macon. Today he runs his businesses out of his den and manages artist Sonny Moorman.

“I’m mostly hawking my books these days,” Willie says of his three books published by Mercer University Press.

- No Saints, No Saviors: My Years with the Allman Brothers Band (2005)

- The Allman Brothers Band Classic Memorabilia: 1969-1976 (2015)

- Diary of a Rock and Roll Tour Manager: 2,190 Days and Nights with the South’s Premier Rock Band (2022)

His last book, Diary, sprang from remembrances Willie would post to his Atlas Records Facebook page, such as this gentle reminiscence from November 1, 2021:

“50 years ago today November 1, 1971, a memorial service was held for Duane Allman at Snow’s Memorial Chapel in Macon, GA. The casket was closed, but Duane was neatly dressed in a long-sleeved shirt and trousers. A joint, a slide bottle and perhaps a silver dollar joined him on his journey. The remaining band members, guests Dr. John, Delaney Bramlett, Thom Doucette, and others joined in playing. Gregg Allman played and sang a solo version of Melissa. Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records delivered a deeply moving eulogy. Like so many geniuses, Duane’s star burned briefly and brightly, yet remains eternal. I still dream of him often.

After several people suggested Willie’s posts could be compiled into a book, he agreed and crafted chronological vignettes in Diary, describing each of the band’s shows, highlighting the venue and other key facts.

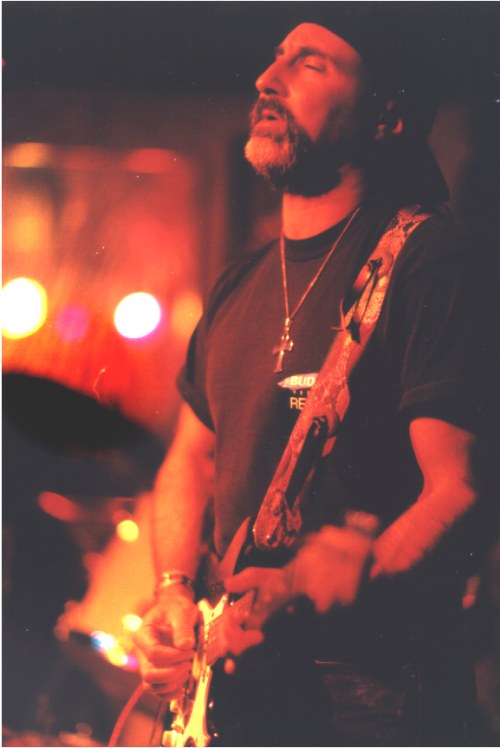

Through all of his roles and his career, until today, Willie is known for his generous support of musical artists, both up-and-comers and established musicians, both clients and non-clients alike. For instance, he made a huge impression on Reddog, a blues guitarist who played with his band around Atlanta starting in the 80s. (Reddog the guitarist is not to be confused with Red Dog, aka Joesph Campbell, who was an original member of the ABB’s road crew.)

Reddog met Willie through Epic records in 1999 when Willie was running Strike Force Management’s east coast office and representing Stevie Ray Vaughn and Gregg Allman.

“Willie was kind and respectful from our first meeting,” Reddog says, “and he continues to be kind today. Through the years when I had a question about the business end of music Willie was always willing to share his thoughts and wisdom. Although he represented some very famous artists, he treated up-and-coming musicians very kindly.”

Reddog, a singer/songwriter who also covers blue standards, remembers being on the road with Reddog & Friends and Willie reaching out to offer the group tickets to see a Gregg Allman or Stevie Ray Vaughn show on their night off. For Reddog, who as a teen was inspired by Duane Allman to play the guitar, being nurtured as an artist by Willie was a waking dream.

“Willie has great insight into the way a creative musician thinks,” Reddog says. “He doesn’t try to change the musician but encourages and points out the path that could lead to an artist finding greater success. Every time I speak with Willie I thank him for taking an interest in my musical career as it has meant so much to me.”

Reddog was included in a 1988 GUITAR WORLD magazine article entitled Who’s Who of the Blues: 50 Bluesmen that Matter. Now a resident of Florida, Reddog has produced several albums, the last one, recorded in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and released in 2022, was titled Booze, Blues & Southern Grooves. Reddog plans to return to Muscle Shoals in the fall of 2024 to record another CD of original tunes, knowing he can reach out to Willie any time and get a thoughtful response.

You can learn more about Reddog’s music and career here. He’s just one example of hundreds of artists over the decades who have been touched by Willie’s kind interest and guidance.

While Willie continues to encourage musicians at all stages of their careers, he also spends time at The Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House, helping to preserve the ABB legacy.

In No Saints, No Saviors, Willie writes about his first day on the job as the ABB’s road manager:

“As I made my way up the walkway at 2321 Vineville Avenue, I realized I was about to embark on a great adventure. This was the “Big House,” the rented home of Duane Allman, Gregg Allman, and Berry Oakley and the official band headquarters. It would also become my home for the next several months. (Pg. 1)”

Richard Brent, Executive Director of The Big House Foundation, lives in Perry with his wife, Megan, but he might sometimes feel like he lives at 2321 Vineville Avenue with everything the museum has going on. The couple moved down from Virginia in 2008 for Richard to work as a construction manager. In 2011, Megan opened a popular eatery/catering service in Perry called The Perfect Pear and she’s also a blues singer with her own group, the Megan Brent Blues Band. That ABB musical circle keeps expanding beyond Macon, even today.

Being a huge music fan, Richard decided to volunteer at The Big House when his construction job was furloughed during the recession. Soon, Richard took a part-time job at the museum and then a full-time job, eventually accepting his current Executive Director role.

“I’m just doing whatever’s needed,” Richard says about his role, being humble about his work and showing that saying Yes to the museum opportunities has changed his life. “This job isn’t something I thought I’d be, but it’s the way things worked out. I do the best I can every day.”

Richard has known Willie for ten years.

“Willie is family,” Richard says. “We’re here for him and any time we have a band-related event, Willie comes on over. On other days he’ll sit in the gift shop and kindly autograph his books for fans.”

The Big House Museum opened in December 2009, and sees nearly 20,000 annual visitors from all over the world. In addition to Willie, other band employees like Tuffy Phillips, former roadie, and Kirk West, Big House founder, photographer and former ABB road manager, spend time at the museum, often surprising die-hard fans who know and recognize them.

“We’re lucky,” Richard says, “to have these family members still here with us and still local to join in and enhance our visitors’ experiences.”

Willie might also show up to attend music performances in the outside pavilion where artists play various genres, not just rock. This year’s Big House concert series is the first since Covid interrupted their original program. The series schedule can be found on the museum’s website and social media accounts.

Future expansion of the Big House grounds will include an events center expected to open in 2025. The museum is also revamping their children’s program, Reach for the Sky, to be held in the new building. The program will offer instruction on various musical instruments, including piano, guitar, and bass. There’s a possibility the program will also be offered to local Macon schools, just like they did with the original “African Drum” program.

“That’s how you spread the word,” Richard says of Reach for The Sky and its promotion of the ABB’s legacy. “Our fan base has gotten older. We enjoy exposing new generations to music and to the museum.”

Fans can also tune into 100.9 The Creek, broadcast from Cherry Street in downtown Macon, to catch Richard and his co-hosts John Lynskey and Kyler Mosely for their Whipping Post Big House Radio Hour every Friday at 7pm EST. They play ABB music — albums and live performances — and discuss the context of the recordings through stories and sharing insider information.

The Big House Museum wouldn’t exist without Kirk West, the ABB’s former road manager and current owner of Gallery West in downtown Macon where Kirk sells his photographs. For 50 years, Kirk photographed the most iconic musical groups and blues artists from all over the nation and then in 1989 he dropped his photography work to become the ABB’s tour manager… for 20 years.

Kirk and his wife Kirsten bought The Big House in 1993 and lived there until selling it to The Big House Foundation in 2006. “When we bought the Big House,” Kirk says, “we wanted to turn it into a rock-n-roll Bed & Breakfast. It was in bad shape, the roof was rotting. After we moved in we learned the city of Macon would require the B&B to have a fire escape and restaurant kitchen installed. Our solution was to not charge folks for staying there. We just put out a collection box so they could pay whatever they felt was warranted.”

Kirsten, who had previously renovated two homes, managed the renovations of the Big House while Kirk was on the road with the ABB. The couple lived in the Big House for 14 years and when Kirsten was ready to move out, Kirk had the idea to turn the house into a museum. He included his personal collection of ABB Memorabilia in the sale of the house, kick-starting the museum’s exhibition content.

Kirk has led an interesting life. Just as Richard said Yes to opportunities at the Big House, Kirk credits his own “Yes” attitude to his many successes. “My whole life, I just kept saying ‘Sure, I’ll try that. I think I can do that. Yeah, I’ll give it a shot.’ I never said no.”

Kirk said Yes to photography as a career, to road managing the ABB, to producing music box sets, to renovating the Big House, to turning it into a museum, to making the documentary Please Call Home, to doing a radio show, to scanning and curating thousands of his photographs taken during five decades, to opening his photo gallery, to hosting monthly music events, etc. The list of his artistic accomplishments is long. All the while, Kirsten has been his biggest support.

Naturally, Kirk and Willie run in the same circles. Heck, they did the same job of road managing the ABB at different times.

“Willie comes to all our various events,” Kirk says. “He’s a solid cat. Still kicking. Neither one of us moves as fast as we once did. But Willie is like the wise old man here in town, and he’s always involved with Gallery West, coming by to enjoy the music on First Fridays in downtown Macon and sometimes to sign his books. ”

Kirk even helped Willie with photographs for his book No Saints, No Saviors, and also for Willie’s ABB memorabilia book.

Thank goodness Kirk is an excellent communicator; we get to hear about his eventful life and what’s currently on his mind through his gallery website and his radio show, Into the Mystic, broadcast on The Creek.

Kirk records his radio show at Capricorn Studios. In each session he tells personal stories as he plays the music that has moved and changed him from one life stage to the next. He’s learned some difficult life lessons and shares it all beautifully, imparting valuable, hard-earned wisdom. Listening to Kirk every Monday evening at 7pm EST is therapeutic. His archived shows are worth listening to, and his photographs are worth visiting on his gallery’s website, in his brick-and-mortar gallery and through his books:

• Les Brers: Kirk West’s Photographic Journey with the Brothers

• The Blues in Black and White The Photography of Kirk West

With the support and hard work of Kirk, Kirsten and hundreds of other people dedicated to starting the Big House, the foundation was set up as a non-profit and these days appreciates support in all its forms, including visitors, donations, gift shop purchases and volunteers. As a reminder from Richard, anyone interested in being a Big House volunteer is welcome to stop by and fill out a form.

You might just luck up and meet Richard… or Kirk… or Willie.

Music & Movies

From a young age, Willie was inspired by music, movies and fast cars.

For years he attended NASCAR races around the South and was familiar with the Middle Georgia Raceway in Byron, where the 1970 pop festival was held, before he arrived there to organize The ABB performances.

During those early years of his road management career, Willie collected classic cars, at one time accumulating 14, which had to be housed in a storage unit.

“As you know, cars need to be driven,” Willie says, “And being on the road so much with the band for so long, I just couldn’t drive them all.” Before selling off his cars, Willie would manage minor mechanical work himself, but never any body work or engine overhauls.

Today, he drives a black convertible 1995 Camaro Z28.

He’s always liked cars, and he still likes fast cars even better.

As a kid in the 40s, though, Willie grew up watching men on horseback in the movies. After visiting his doctor for childhood asthma and allergy treatments, Willie would spend at least three afternoons a week at the movie theatre in Augusta. His mother, Addie Bentley Perkins, was VP of an insurance company so while she worked, Willie watched movies until she came to pick him up.

“Back then,” Willie says, “they would show a cartoon, and then something like the Three Stooges, and then a Western followed by a serial, which was a short action film with a cliffhanger, so you’d have to go back the next week and see what happens.”

In that theater Willie fell in love with movies and so began his dream of working in the entertainment business, specifically Hollywood.

As we know, Willie’s opportunity in entertainment came from the music industry, but that didn’t keep Willie from rubbing elbows with movie folks throughout his career.

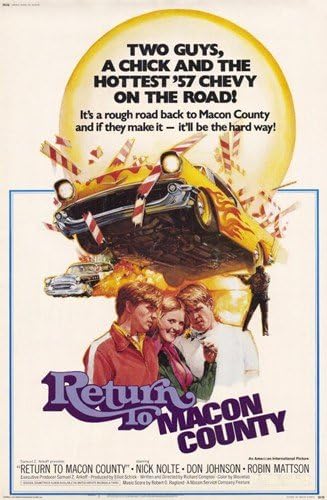

In the 70s, The ABB bought a farm north of Macon where they enjoyed rehearsing, fishing and skinny-dipping. In 1975, a crew came around filming Return to Macon County, a movie set in 1958 and starring Nick Nolte and Don Johnson, both very early in their acting careers, and playing roles as friends and race car fanatics. Race cars were right up Willie’s alley. Willie and the band members befriended Nolte and Johnson and hung out with them during their filming stay.

“They were young,” Willie says of Nolte and Johnson, “and they were fun as we got to know them. We’ve stayed in touch over the years.”

Another actor/filmmaker Willie admires also became a friend… and a huge Willie Perkins fan. Billy Bob Thornton is also a musician with his own touring band, the Boxmasters. Billy Bob invited Willie to attend a Boxmasters 2015 show at the Georgia theater in Athens, Georgia.

“I went out to their tour bus and met Billy Bob before the show,” Willie said, “and then when they were performing, Billy Bob told the crowd that a special guest was in the audience and he talked about me for what seemed like 20 minutes.”

Willie seems surprised that he’d warrant so much praise in public. But Willie has touched many lives over the years, even people who have never met him.

When Willie and Jack Weston published their memorabilia book, Billy Bob Thornton provided this quote on the back cover:

“The cover of The Allman Brothers Band At Fillmore East is the Mount Rushmore of rock album covers. I own signed (by photographer Jim Marshall) prints of both the front cover and the back cover of the best live record ever made. Sometimes I just stand and stare at them — just imaging the gear those cases hauled, even if they were empty at the time of the photo shoot. I examine the bricks in the wall, the added picture of Twiggs. You think I can name the band members on the front? Of course, who couldn’t? But how about the back, the road crew? Here goes… Red Dog, Kim Payne, Joe Dan Petty, Mike Callahan, and Willie Perkins. Not something I looked up on the internet. I’ve just known since I was 15. Thank goodness for this book so I can quit thinking I’m the only one who’s crazy.”

Billy Bob ain’t crazy. Well, he’s as crazy about the ABB and Willie as all the other long-time and new fans are who appreciate the music and the players.

Still Standing, Still Stable

Willie’s work hasn’t been easy, but it somehow came to him in a natural, almost magical way, conditioning Willie to expect good things. Like Kirk West, Richard Brent, and other successful people, Willie saw an opportunity and said Yes to it, but he didn’t take it for granted. Instead, he worked hard year after year and was flexible and creative enough to zig and zag with industry changes.

Willie is still standing and still stable. He’s standing and representing the ABB 50+ years later while also actively involved in The Big House Museum and Macon’s music circle.

Willie is also still standing and representing his 30-year client, Sonny Moorman, a blues artist living in Hamilton, Ohio, who, at nearly 70 years of age, still plays several gigs a week. Sonny is amazed that as a kid from Ohio who grew up loving the ABB, he’s now engaged in the Macon music scene, making trips down south to play with second- and third-generation musicians of original ABB members.

Sonny met Willie in Memphis when he was recording with 706 Records, which is owned by the same people who own Sun Records. The studio recommended Willie as Sonny’s representative and brought Willie to Memphis for their first meeting. Sonny said Yes to Willie.

“Whoever I am in regards to Macon,” Sonny tells me, “it’s all because of Willie.”

That circle in Macon binds together history and current happenings related to folks involved in the “southern rock” explosion of the 70s up until today. Sonny is firmly in that circle.

On May 19, 2024, Sonny Moorman married Lisa Waltman at The Big House. They held their reception party at Grant’s Lounge on Poplar Street downtown. Their rehearsal dinner was at H&H Cafeteria where, coincidentally, Gregg’s widow, Shannon Allman, happened to be dining that day.

Sonny is returning to Macon in September to play an acoustic set at Gallery West on September 27th from 4-7pm. Shaun Berry Oakley, grandson of original ABB member Berry Oakley, will join in as they perform while Willie signs his books.

Willie, Kirk, Sonny. They’ve been running in the same circles for what seems like forever.

“We started out working together,” Willie says about Sonny, “But over the decades we’ve become very close friends.”

“Willie is the remaining Allman Brothers business guy,” Sonny says, “all the others were on the music side and most are gone now. He was the youngest fraud examiner for a big Atlanta bank and he brought to the ABB more financial knowledge and expertise, far above the norm of what other tour managers brought to their bands.”

Sonny loves hearing Willie’s uncensored stories of his road management career. “One time,” Sonny says, “Willie and I were driving a Sprinter van from a festival in central Georgia back to Macon through a biblical thunderstorm and hellish rain, listening to the Pink and Black show spinning 50s music on SiriusXM radio. Hearing those golden tunes, Willie started telling stories. Man, I’ll always remember that trip and those stories.”

Sonny’s Lucky 13 album was named 2020 Blues Album of the Year by Just Plain Folks. “We’re working on a new release now,” Sonny says, “And we’ll be doing the final recording at Capricorn.”

Willie is still bringing people into the Macon music scene, still living in the same house in Macon, and still eating at the H&H cafeteria in downtown Macon. Capricorn’s original studio, just a couple blocks from H&H, was revitalized by Mercer University and launched as a studio and museum in 2019; Famous Studio A has been preserved while a new state-of-the art Studio B records contemporary bands, like Blackberry Smoke, a modern day southern rock/country rock band and cousin to the ABB’s sound. In fact, the group produced the first major album to be recorded at the sound studio in 40 years with their 2020 Blackberry Smoke Live from Capricorn Sound Studios that includes cover songs of Macon legends like the ABB, Little Richard, Marshall Tucker Band and Wet Willie with some of those stars contributing. Gregg Allman recorded with Blackberry Smoke on the track Free on the Wing from their 2016 Like An Arrow album, before his death in 2017.

The Big House Museum is a mile from downtown. Offices at 535 Cotton Avenue, Phil Walden’s former Capricorn Records headquarters where Willie sometimes worked, is just two blocks from H&H. Willie’s Macon is one big music circle and he’s in the center of it, speeding from spot to spot in his Z28 Camaro.

As Willie and I are eating and talking, his astonishing music world of the 70s and 80s falls within a one-mile radius of where we’re sitting at the H&H Cafeteria.

“Looking around town now,” Willie says, “it likes nothing ever happened here.”

But many people know what happened in Macon. The city is right up there with Memphis and Muscle Shoals in its deep-rooted influences on American music. The Bitter Southerner even extolls the importance of those three cities on a t-shirt that simply reads, “Macon, Memphis, Muscle Shoals.”

Starting when Macon was a muddy frontier town in central Georgia, music has been important and celebrated in the area, as described in Dr. Ben Wynne’s Something in the Water: A History of Music in Macon, Georgia 1823-1980.

Dr. Wynne, a music scholar and professor of history at the University of North Georgia in Gainesville, interviewed Willie for the Something in the Water and Willie provided this blurb for the back cover:

“Meticulously researched and incredibly detailed… a fascinating read.”

“Willie Perkins,” Wynne says, “should be on the radar of anyone who is interested in the history of American popular music. His involvement with the Allman Brothers Band and the Capricorn phenomenon in Macon classifies him as a true pioneer. He was an active participant in the genesis of ‘Southern Rock,’ and as a result he has a very compelling story to tell. To say he has lived an interesting life may be a significant understatement.”

This little city of Macon, as noted in Wynne’s book, has always been a hub of music, fostered as a cultural center by Wesleyan College from its inception as the Macon Female Collage in 1838, and by the Georgia Academy for the Blind, with both of these institutions still operating today on Vineville Avenue, just down from The Big House. The Academy has traditionally trained its students in music and instrument instruction from its inception in 1852. And, of course, in more modern times, Macon’s local bars, pubs, and theaters were responsible for Little Richard, Otis Redding, and James Brown’s successful career launches. The development of talent continues to this day!

Capricorn Records, founded by Phil Walden and Frank Fenter, was responsible for attracting hundreds of bands and musicians to Macon in the 70s to not just record at Capricorn but to also live in Macon. Phil Walden once said that living in Macon actually became cool during that era.

The bands and musicians played and hung out at Grant’s Lounge on Poplar Street. Grant’s Lounge is still in operation and still bringing great musical acts to town. Phil Walden eventually opened Uncle Sam’s, a bar and performance venue that saw tons of acts fellowshipping and playing.

Because Willie and Phil kept a close friendship until Phil’s death, Willie recently considered writing a biography on Phil, but then he heard Wynne was working on a book about Phil Walden.

“He’s a much better researcher than I am,” Willie said about Wynne, “so I decided he’s the best person to write about Phil.” Wynne confirmed he is working on the book about Phil Walden. “…I’m in the very early stages of working on that through Mercer University Press. Right now the work on it has barely begun.”

Wynne’s book on Phil gives us all something to look forward to. Meanwhile, he included a chapter on Capricorn Records in Something in the Water that gives a great overview of Phil’s contribution to making Macon the gushing fount of southern music that still flows to this day.

Willie is still here, part of the city’s history, willing to share his story and the band’s stories. But he’s not sitting around waiting for the phone to ring. He receives hundreds of emails a day from fans around the world who view him as a God. And at 84, he’s quite active with a regular gig as a poker dealer at a Macon pub every Thursday night, and with the AMP luncheon club.

“AMP stands for Ancient Music People,” Willies says with a grin. “We get together once a month at different Macon restaurants and tell stories.” The group comprises former music industry folks who assist members moving through their senior years and dealing with occasional money and health challenges.

As for dealing weekly poker games, Willie finds some of that old-time rowdiness — maybe even danger. Early one evening in 2019, as reported by The Telegraph newspaper, Willie was preparing to deal poker when an angry 80-year-old man drove his truck into the pub, trapping Willie under a table. On Facebook, Willie wrote that the truck smashed into the pub “completely destroying the pool table, poker and dart area where I was. He made three passes! I was buried under the table and survived with minor cuts and bruises. Several others were more seriously hurt and sent to emergency room. A miracle no one killed.”

A miracle.

Magic maybe.

The expectation, certainly, that good things will happen to Willie Perkins.

When Willie took the job with the band, leaving behind a secure corporate job, he didn’t know if the ABB would see success or failure. His intuition told him they were going to be something great, but no one knew for sure, not even Willie. He took a gamble. Some might say he took a long-shot when he altered his career path.

In part two of a 2021 interview with Marshall Tucker Band lead guitarist Chris Hicks, as part of Chris’ Southern Rock Insider YouTube series, Willie discusses his thoughts on being part of the ABB:

“I wouldn’t go back and change anything from when I made the decision to go with those guys. Like I say, there were ups and downs and triumphs and tragedies, but I made friends for life. The music is going to outlive us all. It was a great time to be involved.”

“I thought Willie did one of my favorite interviews,” Chris says.

Chris is a guitarist’s guitarist, admired as much for his singing voice as for his guitar playing, which is exemplary. He grew up in Lizella, Georgia, a small community on Macon’s border and the site of Idlewild South, the Allman Brothers Bands’ farm.

At 16, Chris received a phone call from Jaimoe, ABB’s drummer who had heard about Chris’ local band and his guitar work. Jaimoe asked Chris if he wanted to jam.

“That phone call was freaky in its own right,” Chris says, laughing “not to mention how freaky it was to jam with Jaimoe again and again.”

Jaimoe’s call to jam was the beginning of Chris Hicks’ journey from playing bluegrass with his grandfather and into the world of Southern Rock, where he continues to live, on the road with Marshall Tucker for 27 years now and also working on his own music.

Chris has met or performed with every major player of the Southern Rock genre, plus many other artists in other genres. A fast thinker, Chris’ curiosity in all things drives his zest for life. It’s easy to see why people want to be part of the Chris Hicks fan club, and to jam with him.

Jaimoe, the only surviving member of the original ABB, likes to brag to folks, “I’ve been knowing Chris since before he could grow a mustache.”

Chris met Twiggs Lyndon back in the day but he only met Willie Perkins a few years ago, just before taping their interview. “I’ve always admired Willie from a distance,” Chris says. “Twiggs and Willie started the whole idea of road managing. They wrote the book on taking something abstract like touring and bringing it into the real world.”

To hear more details about Willie’s experiences of being on the road with the ABB, watch Part I and Part II of Willie’s interviews with Chris.

Calculated Risk

Willie took a chance in 1970 and worked smart and worked hard, contributing to Macon’s music scene of yesterday and today. He’s an integral part of that circle, linked to The Big House, H&H Soul Food Restaurant, Kirk’s Gallery West, Grant’s Lounge and, by extension, Capricorn Studios, 100.9 The Creek, the Otis Redding Foundation, and other active music traditions.

Macon’s motto, after all, is “Where Soul Lives.”

Willie’s gamble – or more like a calculated risk – paid big dividends. He launched his career into the music industry and into Macon’s music history. He also launched his current place in the city’s circle of supporters who are continuing its musical traditions… and creating new ones.

Here’s to Willie and to Macon.

May the circle be unbroken.

A special Thank You to my friend Reddog, the blues guitarist, for suggesting I spotlight Willie Perkins, and for connecting me with Willie. And a special Thank You to Willie for saying yes and participating! A big shout out to my neighbor Tracy S. for welcoming me to the neighborhoood (and saving me from my cantankerous push mower) by offering to cut my grass, which freed me up to write about Willie. Appreciate you, Reddog, Willie and Tracy!

I dedicate this article to my sister Cathy M., a long-time, huge ABB fan who finds great comfort in listening to their music. We grew up in Warner Robins, GA, in the 60s/70s so the ABB is in our blood.

Sending love and light out into the world. Hope you catch it!

RESOURCES

William Perkins Facebook

Chris Hicks of Southern Rock Insider Interviews Willie Perkins:

+Video: A Conversation with Willie Perkins, Part 1

+Video: A Conversation with Willie Perkins, Part 2

MACON’S MUSIC SCENE

The Big House Museum, 2321 Vineville Ave, Macon, GA 31204

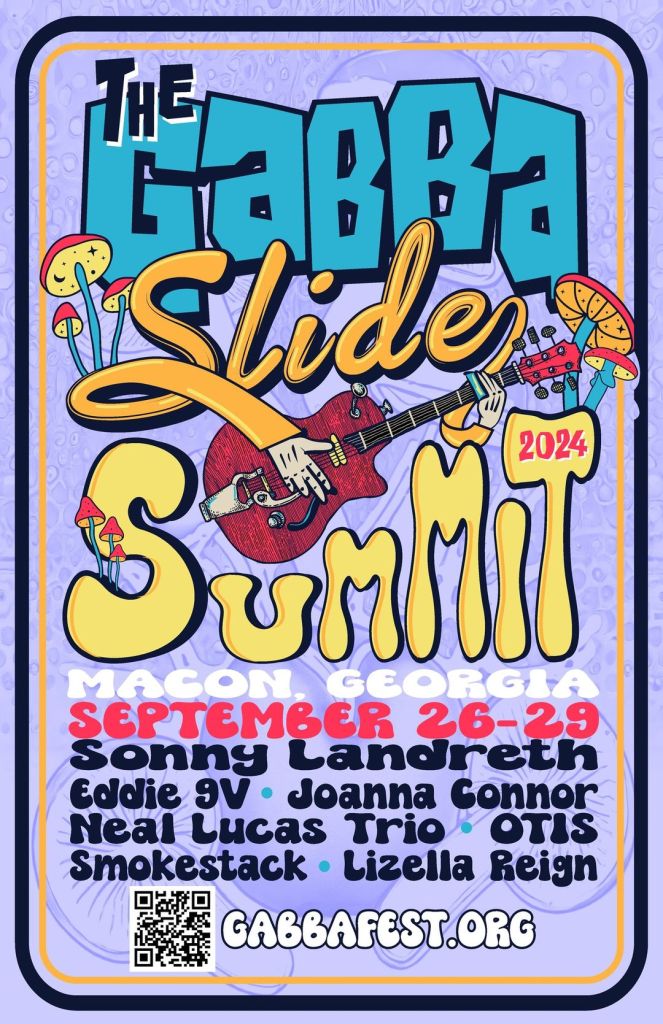

The Georgia Allman Brothers Band Association (GABBA) – UPCOMING EVENT: Sept. 26-29. 2024

H&H Soul Food Restaurant, 807 Forsyth Street, Macon, GA 31201

Gallery West, 447 3rd Street, Macon, GA 31201

100.9 The Creek, Broadcasting from 543 Cherry Street, Macon, GA 31201.

OTHER MACON LEGENDS

The Otis Redding Foundation/Museum, 339 Cotton Ave, Macon, Georgia 31201.

UPCOMING EVENT: 3rd Annual King of Soul Festival, Honoring Otis Redding, September 6 -7, 2024

The Little Richard House Resource Center, Tour Little Richard’s childhood home.

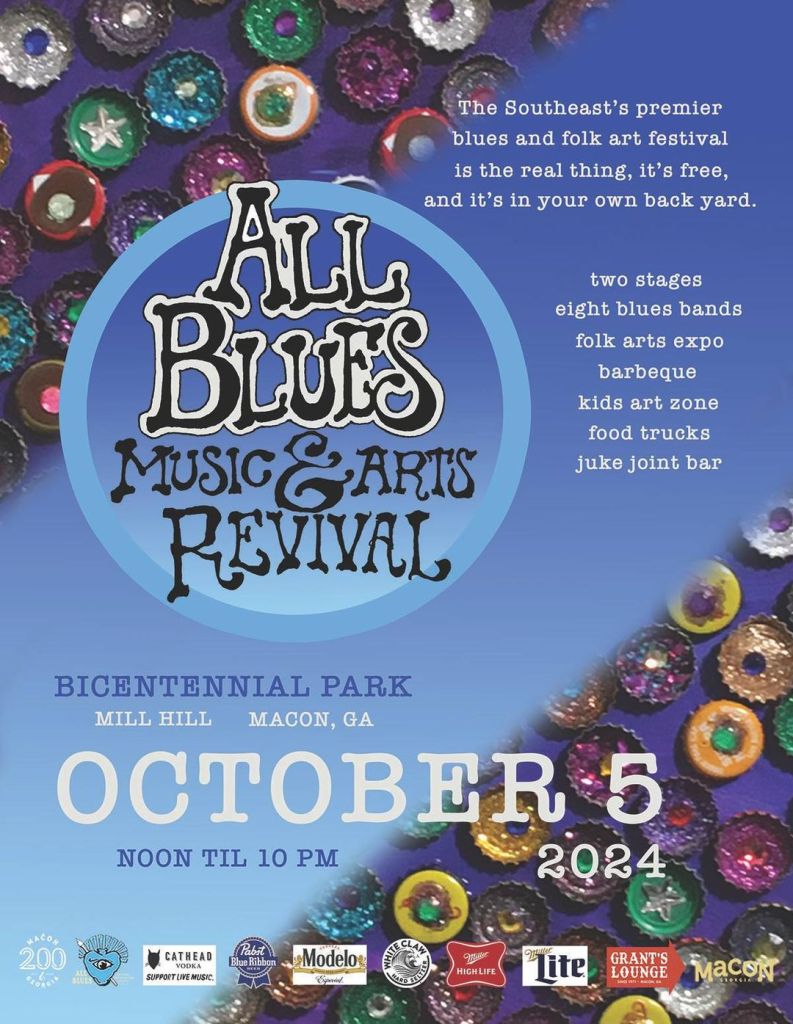

All Blues Music & Arts Festival, Oct. 5, 2024