New Orleans is celebrating its 300th birthday this year and the entire city continues to be the ultimate creative space. Dripping with history, NOLA is often thought of as a party town, especially along Bourbon Street in the French Quarter. But there is much, much more to New Orlean’s culture than alcohol.

Foremost, it’s the birthplace of Jazz and hometown of Louis Armstrong and Fats Domino… and Harry Connick, Jr., … and many other amazing musicians from the right and left banks of the Mississippi River.

Though it’s a strong one, Jazz isn’t the only draw to the Crescent City. There’s the food, cajun and creole and stuffed with fresh seafood. And beignets anytime of the day. Yes, BEIGNETS!

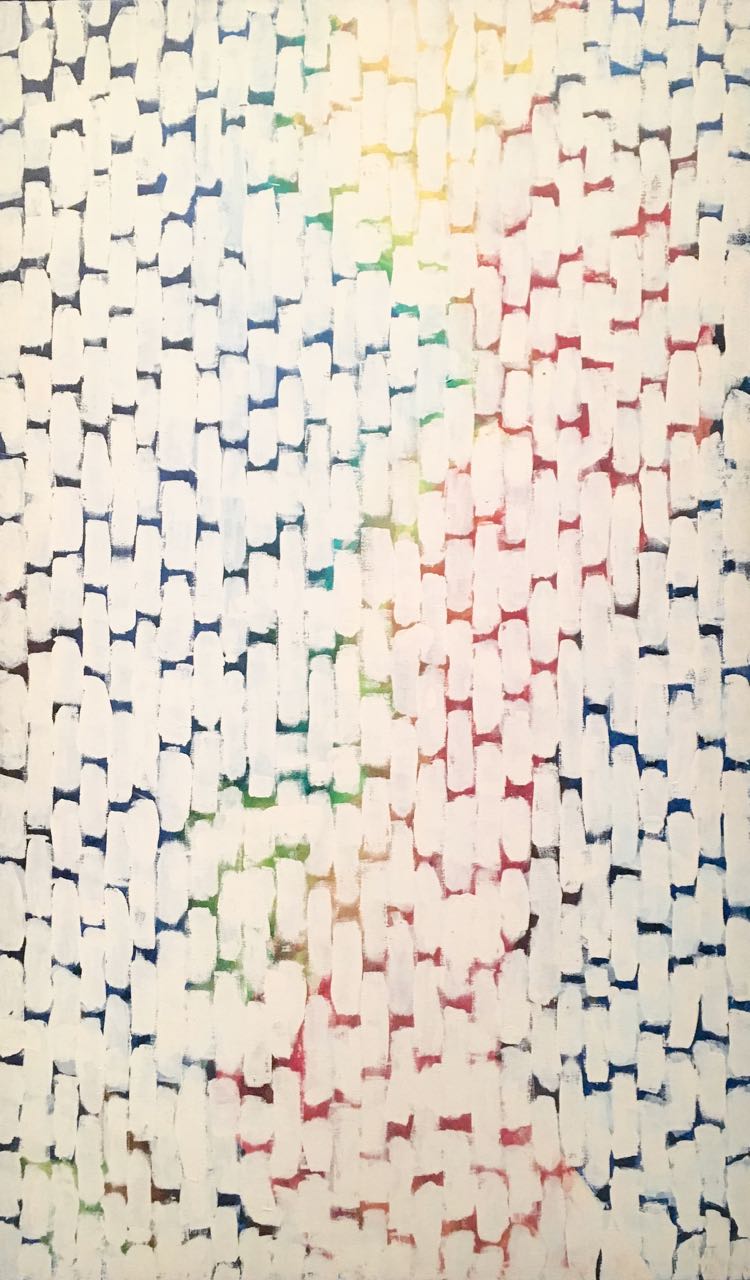

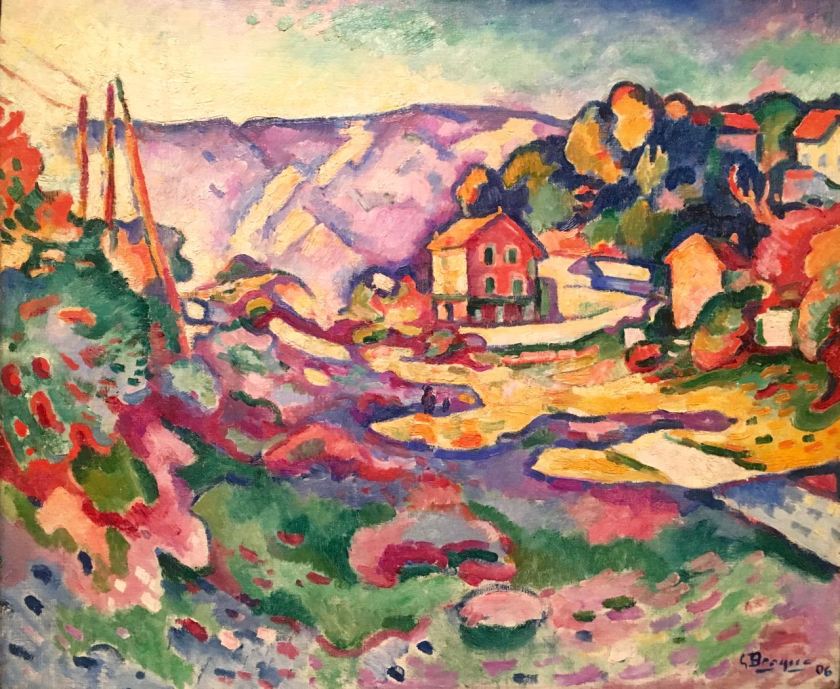

Like most grown-up cities, New Orleans also appreciates visual artists. On a recent trip to NOLA, I couldn’t resist visiting the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), both of which allow patrons to photograph their art!

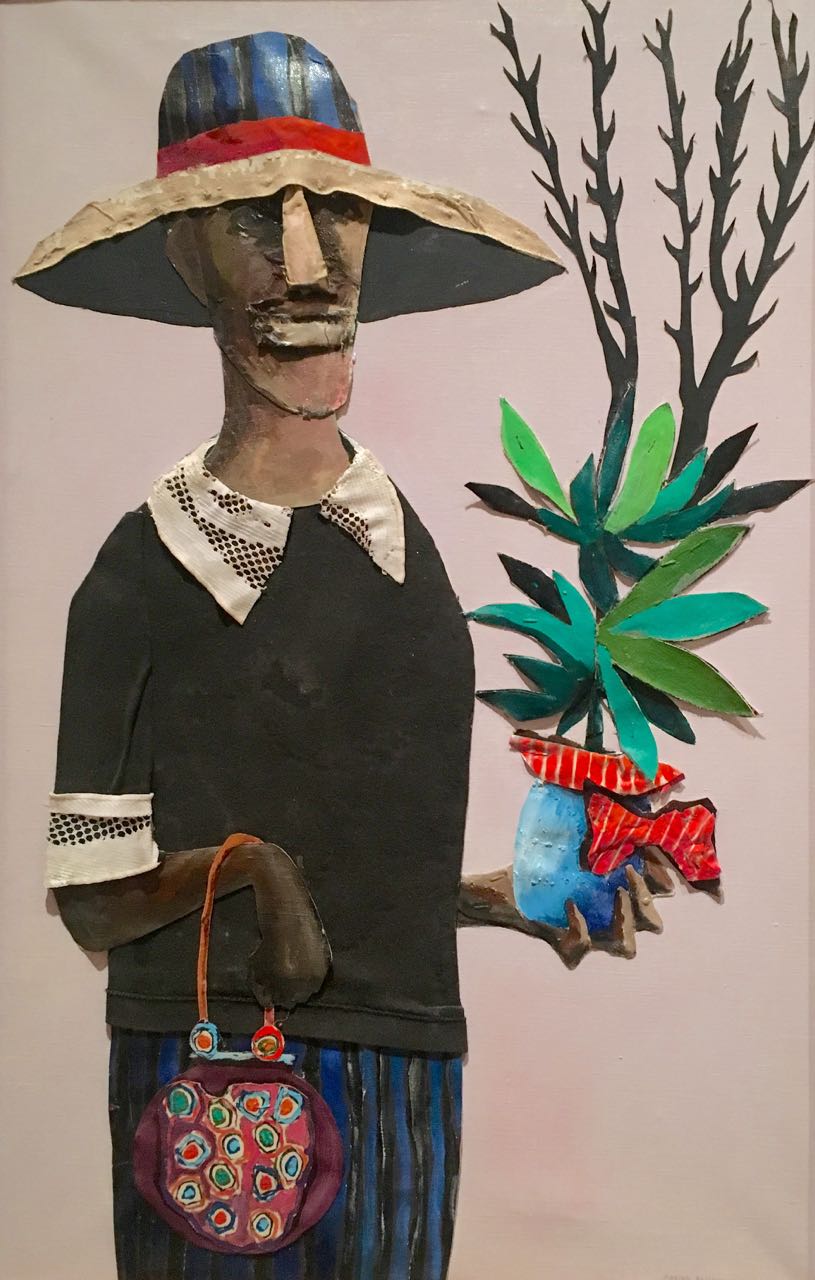

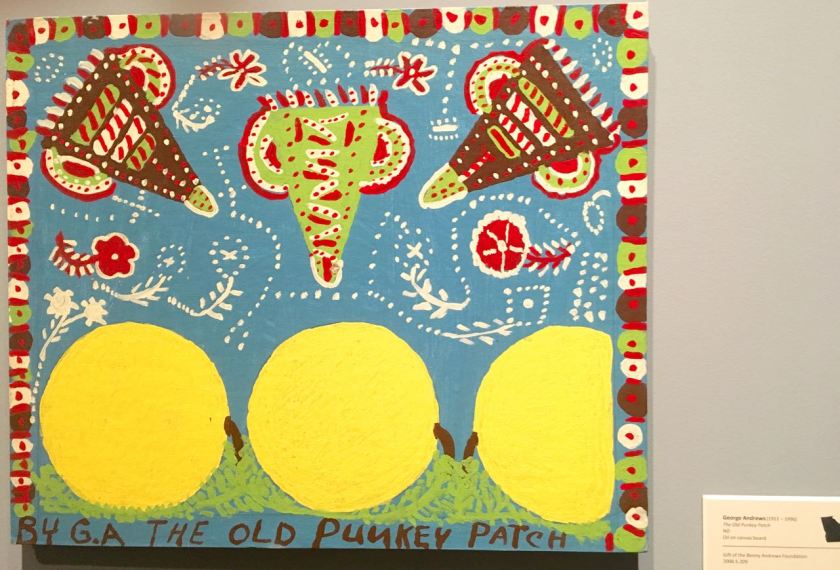

At the Ogden, I was thrilled to find a wing of “Southern Vernacular Art” featuring many oil and collage works by Benny Andrews. I can’t recall where I first saw a painting by Benny Andrews, but I liked his style and subjects and was hooked. When I researched Benny, not only did I find out Benny was from Georgia (like me), but he also attended Fort Valley State College (like me)! While I didn’t graduate from Fort Valley State College, I’m proud to have spent the academic year 1983-1984 at this remarkable historically black college in the heart of Georgia.

Benny was born in Plainview, Georgia, in 1930, and his father, George Andrews, was a sharecropper and a self-taught artist. (Both of my maternal grandparents, and their parents, were sharecroppers in South Georgia). After graduating high school, the first in his family to do so, Benny joined the service and later used his G.I. Bill to study at the the Art Institute of Chicago (the article “240 Minutes at the The Art Institute of Chicago” features a Benny Andrews painting!).

Benny was an activist and advocate for African-American artists. To my delight, the Ogden had several of his collages made using fabric and wallpaper. Some of the collage features are so 3-D, they cast shadows, as do some of the deep frames.

Following are Benny’s collages, plus other works that caught my eye at the Ogden and NOMA. Enjoy!!